The right to protest – what are the limits? The case of Deakin University

Leigh Naunton

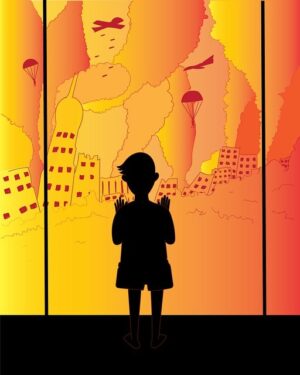

Recent student protests including one at the Burwood campus of Deakin have raised this question. The students are protesting universities’ alleged links to military equipment manufacturers who supply Israel. They set up an encampment at Deakin Burwood and at Monash Clayton and occupied a building at Melbourne University.

It was reported on 28th June that several Victorian universities have warned students of potential suspension or expulsion and that nine students at Monash and two each at Deakin and La Trobe had been issued misconduct notices, with one already suspended. The students say that Deakin has given formal warnings to every student the university could identify as having participated in the encampments.

The universities state support for the right to protest. Of course, this has limits in society. Violence and property damage are subject to legal penalty, and under the Commonwealth’s Racial Discrimination Act and Racial Hatred Act, it is unlawful to do or say something in public that is reasonably likely to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate a person or group because of their race, colour, or national or ethnic origin.

Trespass is also unlawful but was tolerated to some extent by the universities including Deakin, perhaps in part due to their unwillingness to involve police and the police being unwilling to enforce the law when protest is seen to be generally peaceful.

On the other hand, there are laws and rulings which support freedoms. The Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 states that rights may be limited by laws and rules only so far as can be demonstrably justified taking into account all relevant factors.

The implied right to freedom of political expression under the Australian Constitution also operates as a freedom from government restraint rather than a right conferred directly on individuals. Moreover, insisting on these rights can mean expensive legal challenges against powerful adversaries, risking adverse and potentially devastating costs if the case is lost.

On 16th May the Deakin Vice Chancellor emailed all staff and students stating among other things, ‘I want again to be clear that the instruction is not to stop protesting but to remove the encampment. We are taking this action based on our unwavering commitment to the security and safety of everyone in the Deakin community and their right to unimpeded access to the Burwood Campus.

In his email, the Vice Chancellor said, ‘The University is committed to our Code for Upholding Freedom of Speech and Academic Freedom. The ability to engage in protest, political discourse and debate on Deakin campuses is part of our role as a university. But there is no place at our university for the unacceptable language and behaviour that we have seen from the protestors, including those we believe are not Deakin students. This behaviour is in breach of Deakin’s code of conduct. The continuing presence of the encampment at Burwood is increasingly compromising the right of those in our community to access and enjoy a typical learning and work environment free of impediment, intimidation, threat and harassment.’

Now it is possible or even probable that there had been language and behaviour that was in breach of the code of conduct. However, when I visited the campus on two occasions, the first on the same day as this edict, the only impeded access was due to the university stationing security guards and pole and tape barriers at either end of the broad walkway beside which at a short distance was the encampment. One student said to me that they supported the protest but were on a scholarship and too scared to be in a photograph. This could also be an indication of the chilling effect of the University’s response.

In the case of student protests against the actions and policies of their universities, the students are the underdogs and the universities’ stated commitment to the right to protest may be less than robust.